IN THE NAME OF THE FATHER AND OF THE SON AND OF THE HOLY SPIRIT.

AMEN.

P r e f a c e

___________________________________

1. SOLUS CHRISTI SKETE of the MONKS OF NEW MANJAVA (and its dependent Sketes) is a stavropighial monastery under the Omophorion of His Beatitude the Metropolitan Prime Bishop of the Autonomous Ukrainian Orthodox Church in America.

2. The Fourth Ecumenical Council of Chalcedon established canons for the inter-relationship of the Monastery and the rest of the Church. Therefore, the Hierarch has the right of canonical visitation, to impart the customary blessings when called for, to ordain monks presented to him for Sacred Orders, thereby making certain that each skete has at least one priest. He insures that the integrity, purpose and goal of the monastic life are preserved free of interference for the best interest of the monks.

3. The term MONK and/or NUN is applied to those whose lives are free of division or fragmentation, whose lives are one, unified, integrated, stable and living together toward attaining God-like unity in the perfection of divine love.

4. Through asceticism, hesychasm and faithfulness in observing this Typicon, a monk seeks to attain spiritual transformation (metanoia) and divinisation (Theosis) in the Holy Spirit.

5. Accordingly, the aim of Solus Christi Skete of the Monks of New Manjava is to strive to attain perfection within the brotherhood through an evangelical life and the practice of the evangelical counsels. We illustrate and fulfill our desire to foster true peace and compassion as the genuine roots of justice in the world through our search for God within our brotherhood and with all persons of good will, in the Holy Orthodox Church, by personal repentance, that is, changing our minds and hearts, our manner of life, in favor of progressive interior responsiveness to the Word of God. To this end, no skete of Solus Christi may attach more than three monks living the communal life.

6. The Sketes of Solus Christi of the Monks and Nuns of New Manjava follow the prescriptions of the Rule of Theodosius of Manjava, and the tradition of Ukrainian monasticism.

P a r t O n e

___________________________________

S t a g e s o f

M o n a s t i c L i f e

CHAPTER 1

Novice

7. Those interested in entering the Monastery must be at least eighteen years of age and must have attained reasonable growth both psychologically and emotionally as well as intellectually, and they must be in reasonably healthy physical condition, before they can hope to embark on the monastic life. Each candidate must make a request to the Hegumen (Abbot) who will determine a date at which time the aspirant will join the Monastery and participate in the monastics’ daily life.

8. The preliminary requirements having been met, the Hegumen will introduce the candidate to the Community and inform everyone about the time-frame for the probation period before the commencement of the Novitiate.

9. The probation period having passed, the Hegumen consults the Monastic Council and then approves the acceptance of the candidate as a novice.

10. The NOVICE is received by clothing in the tunic, leather belt and skufia. The Novice lives with the rest of the monastics under the guidance of the Hegumen who may assign the Novice a spiritual guide. With the others, the novice must fulfill the obligations of life and discipline of the Monastery.

11. The novice must spend at least one year (up to three years, traditionally) as an apprentice in the spiritual life. During this time, the novice is introduced to the monastic ideal and the rudiments of monastic spirituality. The novice cultivates the necessary virtues of monastic life, openness of heart wit the Hegumen and charity towards the monastics.

12. The novice will be instructed about monastic spirituality, coenobitic life, the Typicon, the Spiritual Testament and Rule of Theodosius of Manjava, the Divine Liturgy, the Scriptures, the History of the Church and sacred singing.

CHAPTER 2

Rassophore Monk

13. The Novitiate period being over, if the Hegumen accepts the novice, the novice will be received as a rassophore monastic. Therefore, the novice then makes a commitment to live permanently within the monastic state, renouncing secular life to live in obedience, poverty, chastity, piety and stability and to achieve the evangelical life of prayer and work.

14. The monastic is tonsured, given a rasson (outer garment) and a klobuk. A new name is also given as a symbol of the monastic’s new life in Christ.

15. A monastic may remain as a rassophore all his/her life and live within the community of monastics without ever making a monastic profession into higher degrees of monasticism.

16. The rassophore, not being a professed monastic, may be released from his/her monastic state by the Hegumen who has the authority to bind and unbind.

CHAPTER 3

Stavrophore Monk

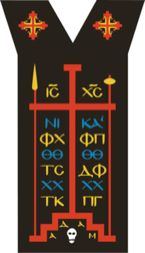

17. After three years as a rassophore, the Hegumen may, after consulting the Council, admit a monk to monastic profession within the second monastic degree: the Small Schema. From this point on, the monk is a stavrophore monk, which means “bearer of a cross.” He is then tonsured and consecrated to God for the rest of his life. He receives the royal mantle (mandias), the paramandias, a hand cross and a pectoral cross worn under the tunic.

CHAPTER 4

Megaloschema Monk

18. After many years of monastic struggle, a stavrophore monk will make profession into the third and last monastic degree: the Great Schema. His new life is oriented towards more austere penance, greater monastic labor and cutting himself off even more from the world.

19. The Hegumen or Hierarch performs the rite. His name may be changed, again, and receives a long scapular that bears the emblems of the Cross and the Passion and is worn over his tunic. Having attained this higher degree, he is assigned a new work obedience more closely related to his new life. While still living within the Monastery, he lives in greater isolation, practicing strict fasting and mortifcation, spending more time in personal prayer, especially with the Jesus Prayer.

CHAPTER 5

Monks Who Are in Sacred Orders

20. Since the monastic life is not clerical, there is limited need for monks to be ordained to either the priesthood or diaconate, and they are chosen to fulfill the needs of the Monastery for the celebration of the Divine Services and any parishes attached to the sketes.

21. Monks who are to be ordained are chosen by the Hegumen with the approval of the Council. The Hegumen presents the candidate to the Hierarch for Holy Ordination.

22. Ordination imposes an additional burden of service upon the monk who is ordained, and he must, therefore, be qualified for this service by his intelligence, bearing and love for the Liturgical Services.

23. The Hegumen, if a Hieromonk, may ordain Monks to minor orders. Otherwise, it is the Hierarch who ordains to minor orders.

24. A monk who is ordained to the diaconate is called a Hierodeacon (deacon-monk); a monk ordained to the priesthood is called a Hieromonk (priest-monk).

25. Those raised to sacred orders acquire no special rights or distinctions in the community by virtue of their ordination, but take their places as they did before, according to profession, whenever the recognition of such seniority is called for.

26. Deacon and priest monks, ordained only for the needs of the Monastery, may also serve the needs of the faithful who visit our Monastery.

CHAPTER 6

Forms of Monastic Life

27. Likened to a stone which must be polished, monastic life brings an ointment of mutual love and understanding to refine our souls.

28. Through the eremetical life and that of the anchorite have historically been linked with monasticism in general, our life is semi-eremitical. As St. Basil states, we can hardly give evidence of our compassion and love if we cut ourselves off from each other, if we escape the daily contradictions or our wishes arising from the shear reality of common life.

29. However, a monk may pass into eremetical life as long as he can be autonomous and support himself. Hermits still belong to the Monastery through their profession of vows and may be asked to assist in various ways.

30. If a monk feels that he is called to the eremetical life, the Hegumen will evaluate his capacities to solitude and will insure that the request has nothing to do with avoiding the constraints of community life. Any monk who no longer lives with the members of the Community is still under obedience to his Hegumen.

CHAPTER 7

Monasticism Related to Other Institutions

31. St. Nil of Sinai describes the monk as one separated from all while in harmony with all, who considers himself one with all.

32. Monasteries of our Orthodox tradition have never been aloof from people, nor have they known strict monastic enclosure. In fact, our tradition places monastic life in real relationship with the faithful as well as with the unbelievers who stream through our gates.

33. Nevertheless, a certain amount of seclusion and solitude, as well as silence, is indispensable for the integrity and stability of monastic life, so that relations with the world at large should not constitute a detriment to this. Accordingly, the actual cells and private gardens of the Monastery are not to be opened to those who do not belong to the monastic life.

34. Hospitality should be synonymous with monasticism, and our Monastery must always sensibly see to its serious cultivation.

35. In the deserts of the old world, the first monks and nuns carried on the prophetic ministry of Israel with a renewed vigor. Thus, their lives bore witness to the essential Christian message before a civil and ecclesiastical world that often suffered from secularization, political intrigue and expediency. They were, thereby, witnesses of evangelical repentance and of salvation meant for all.

36. Thus, a monk must be the salt of the earth. For this reason, the Monastery is accessible to all so that they may savor its life, its worship and its message of evangelical love.

CHAPTER 8

Civil Authorities

37. As a “moral person” in the midst of a pluralistic society, we conform to the civil laws pertaining to not-for-profit religious organizations, and, in general, with all such legislation which is not contrary to conscience, the divine law and the teachings of the Fathers.

38. Our Monastery and its dependent sketes are incorporated according to the civil laws of the State of Wisconsin and are registered as a 501(c)(3) tax-exempt organization with the Internal Revenue Service of the United States of America.

P a r t T w o

___________________________________

Internal Regimen of the

Monastic Brotherhood

CHAPTER 1

The Hegumen

39. The Hegumen is the head of the monastic family. His is the authority of father. In the fullness of its signification the name of the father belongs only to God. The brother who receives the mandate to guide the community does not carry it as a name which belongs to him, as something of his own, but as a sign of the divine paternity of which he is the minister and the servant. He must be the most zealous, humble, meek, long-suffering, self-restrained, loving the brethren, and, above all, loving God and fearing God and keeping his commandments and loving the monastic rule and keeping the customs and traditions that this holy monastery has observed from the beginning.

40. It belongs to the father, as the representative of God, to discern God’s will and to make it known to the brothers. In order to discern well, the Hegumen must detach from his personal views and his own will. He must be the most obedient to all that God commands, the most attentive, and the most docile to the inspirations of the Holy Spirit. He must not be overburdened.

41. The voice of the Spirit sounds also in the hearts of the brothers. The Spirit speaks through each of them individually and through the whole group. It is the task of the father to listen to that voice. The father must also remember that he stands in the place of the Good Shepherd. He must take special care for the weaker brother and he must know that each human life has times of trial, crisis and tiredness.

42. The Hegumen is the guardian of this typicon. By his life he sets an example of faithfulness to its prescriptions, especially to its spirit. He may change or make additions to the typicon as he deems necessary, having consulted the council.

43. In accord with the council, the Hegumen receives and tonsures candidates, and after a vote of the community he admits novices to the profession. Similarly, he appoints members of the household to specific assignments, and presents the local bishop with candidates for orders. The Hegumen has the obligation to see that newcomers are cared for spiritually and materially, and that the spiritual formation of the novices is taken care of.

CHAPTER 2

Election of the Hegumen

44. The father of the monastic Brotherhood has been called only for a time, a time of sowing, of planting and, if the Lord wants this, of reaping. His function is not necessarily for life. The passion of God’s will, will incline him to give up his function as soon as he is no longer able to carry the burden. This may be because of age or infirmity, or if a successor can bring a renewed fervor to the task. On the other hand the Hegumen should not decide too easily to resign.

45. He should examine carefully the state of the community and hear the opinions of the brothers. In order to leave all liberty of action to his successor, he could retire for a while to another monastic place. But it is beautiful to return and to continue the work he has started in incessant prayer, by the merit of his example, and finally by his death. A part of his task remains and not the least part.

46. If the Hegumen resigns for some serious reason or if he dies, the monks will inform the local bishop and will gather under the bishop’s presidency to elect another superior. A Hegumen will be chosen by a two-thirds vote of the community and, in principle, is elected for life. At the time of his election it is not necessary that he be a priest.

47. If for some reason the community cannot agree upon a new Hegumen, or if the election of a new Hegumen is not feasible at the time, then the community will elect, within a month and by a two-thirds vote, one of the members of the community to act as superior. He is to be elected for a period of six years and may be re-elected for as many successive terms as the community sees fit.

CHAPTER 3

The Monastic Council

48. From the earliest times, even when they were scattered throughout the deserts, monks came together in council to discuss common concerns, both spiritual and material.

49. The authority of particular monastic councils varies from place to place and from time to time. In our community the professed monks form an advisory council to advise the hegumen on all matters of importance as necessities. The Hegumen convenes these meetings as necessary, but he should call one at least once each month.

50. The council has the right to elect a new superior. It also advises the superior on:

(a) the acceptance of candidates,

(b) the reception of the novices,

(c) the profession of monks (for which they have a decisive vote),

(d) the ordination of monks,

(e) changes or additions proposed for the typicon.

51. If the council is opposed unanimously to any of the above, the Hegumen shall not act contrary to its advice.

CHAPTER 4

Other Monastic Offices

52. Tradition provides other offices for the spiritual, economic and liturgical aspects of monastic life, in order to assist the hegumen in the administration of the community and to free him for weightier matters.

53. To assure the smooth order in the community, the Hegumen appoints one of the monks as prior. In the absence of the Hegumen, the prior acts as the vicar.

54. The econom or treasurer will be appointed by the superior for the administration of the finances and other material affairs of the household.

55. The ecclesiarch sees to the physical order and cleanliness of the chapels, as well as to all that pertains to the celebration of the divine offices. Together with the choir director and the officiating clergy, he interprets the liturgical typica for the various offices.

56. The director of the choir is in charge of the choral needs of the various offices. He appoints the weekly celebrant and the readers for the various offices.

57. The guestmaster and cooks are also appointed by the superior so that the very important aspects of hospitality and nutrition will be cared for assiduously. Let the table at all monasteries of Solus Christi always be simple, wholesome and appetizing.

P a r t T h r e e

__________________________________________

M E T H O D S O F

M O N A S T I C L I F E

CHAPTER 1

Monastic Prayer

58. Jesus lived in the presence of his Father. Nothing was lacking in his attitude of

total commitment, his hymn of adoration and thanksgiving, or his intercession for all. Certain times of his life were more exclusively consecrated to wordless or to formulated prayer. As a devout Jew he prayed openly in the Temple, in the synagogues and before his disciples. He prayed also in deserts and on mountains. From this uninterrupted relation with his Father flowered his life as Son and, in time, his words and his works.

59. We are brothers and sisters of Jesus Christ. He invites us to filial relations with our Father: “In very truth, I tell you, if you ask the Father for anything in my Name, He will give it to you . . . Ask and you will receive, that your joy may be complete” (John 16:23-24). Moreover, he asks a constant vigilance: “Be on the alert, praying at all times for strength to pass safely through all imminent troubles and to stand in the presence of the Son of Man” (Luke 21:36). In this call to prayer Jesus addresses all his own and the special vocation of the monks is included in it.

60. The relations with God are so essential for the life of the Church (the Mystical Body of Christ) that it is convenient that some members consecrate themselves totally to this. The Spirit guides them to solitude, as the Lord was guided, in order to realize with greater freedom and intensity that continuous prayer to which all are invited. The creator of monastic prayer is the Holy Spirit. The Spirit makes us one with the life of Jesus before the Father, and guides us on the ways of interior unification until we respond fully to our profession. Inspired and animated by the Spirit, the monastic order forms within the Church a school and a house of prayer. This is one of the ways to fulfill the desire of the Father to have ‘true worshippers’. It is a vigil of prayer which has to be continued through all the vicissitudes of this world until the parousia of the Lord.

61. We are called to consecrate our life to prayer. The Holy Spirit must teach us according to the will of the Lord, and must support our weakness. If we surrender to the Spirit that Spirit will dwell in us as in the Temple, and will awaken and sustain our prayer; the Spirit will pray in our hearts. Coming from God, the Spirit will bring us back unceasingly to Jesus and the Father, and will develop within us a special ear for the teachings of the saints on prayer and for the advice of those who are familiar with its paths.

62. As mandated in the Spiritual Testament of St. Theodosius, the Monks of New Manjava, Solus Christi Skete, learn and profess unceasing prayer, that is, the remembrance of the name of Jesus. Standing and sitting and lying, in their cell and in the Temple, at work and at table and on the road, continuously in their mind, with their thought or their lips they call out: Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner. In this way, all invasions and entries of extraneous thoughts and assaults will be cut off.

63. The two pillars of such wordless prayer are the understanding of God as foundation of all that is, and the awareness or consciousness that all is already there. It is this Hidden Ground of Love, in which we are at all times -- in which we find our identity, our uniqueness and our interrelatedness. Spending time in prayer, therefore, must not to be looked upon as a means of achieving this oneness, but of recognizing that it is there.

64. The sketes of Solus Christi, the Monks of New Manjava, have their own liturgical Typicon. In accord with Jewish and early Christian tradition we have the Orthros (Office at Dawn) and Vespers. On weekdays our Office at Dawn is followed by the Divine Liturgy. In addition to this we have times of prayer at midday and in the late afternoon.

65. The life of prayer finds its completion in sacrifice. This was the case for all the nations and especially for the patriarchs and the Jewish people. Since Jesus Christ celebrated, in this world during the Last Supper and on the Cross, the sacrifice of the New Covenant, it has become the focus of the relations of mankind with God.

66. As mandated in the Rule of St. Theodosius for the Monks of New Manjava, in all Solus Christi Sketes, the rule of prayer in church is to be in common, on a mandatory daily basis, and generally, without singing: Vespers, Compline, Matins, and the Hours. The Divine Liturgy, when it is possible, is to be sung softly and devoutly. If there is no singer, the cherubic hymn is to be read three times in a drawn-out manner and in unison, twice before the entrance and once after. Similarly, the communion verse, but with faith and the fear of God. For Vespers, the strophes are to be taken from those that are available, sometimes in the monastic manner, sometimes the akathist, sometimes of the church. If there is an Octoechos or Menaion, the service is to be taken according to the proper order (Rule of Theodosius of Manjava Skete).

CHAPTER 2

Monastic Work

67. The need to work is the common lot of all mankind and simply part of the natural order of things. The first monks did comparatively little in the way of external labour. We hear of them weaving mats, making baskets and doing other work of a simple character which, while serving for their support, would not distract them from the continual contemplation of God. Under St. Pachomius manual labour was organized as an essential part of the monastic life. Since it is a principle of monasticism that each skete shall be self-supporting, external work of one sort or another has been an inevitable part of monastic life ever since.

68. From the beginning of monastic life, work has always been included in the monk’s daily life. Work has always been a hallmark of the monk — any kind of work, manual, clerical and intellectual — but always done with care and reverence.

69. Throughout history, our predecessors in monastic life have taught that work is not only required to sustain oneself and the community, but that it is equally important as a means of self-discipline and individual growth as an adjunct to prayer and worship.

70. Work, therefore, is part and parcel of our life, first of all, because it is essential to monastic life in general.

71. In its work, the monastic Brotherhood must utilize the creative talents, intellects and academic formation of each monk in a way that not only supports the monastic Brotherhood financially, but which also witnesses to the spiritual values by which the monastic Brotherhood lives. For example, our brotherhood allows the monks and nuns qualified to do so to work outside the monastery as physicians, nurses and teachers. In this way, our work becomes a means of monastic witness. Whenever possible, and if not detrimental to the sustenance of the community, the Brotherhood should work together, for work in common fosters and nourishes that unity which is the hallmark of monastic life.

72. Let it be clear, however, that in whatever work we engage with the blessing of the Hegumen, we must remember that the monastic approach to work is essentially different from that of the world-at-large, where profit, competition and status are the primary motivations.

73. Just as all goods are held in common, so also are all monies derived from our honest labor in order to insure the benefit of all, not of the individual. Monastics must have the blessing of the Hegumen in order to keep any personal gift received. By virtue of the monastic vow of poverty, donations, as well as any wages earned and inheritance(s), must be given to the Monastery.

CHAPTER 3

Law of Renunciation

74. Our Lord, God and Savior has told us that anyone who would be His disciple must give up all that he has, embrace his cross and follow after Him. But, to be a disciple of Christ requires steadfastness and perseverance, in a word, total honesty, total purity of heart. Thus, poverty, chastity, obedience, stability and unceasing prayer enable us to practice this discipleship without being overcome by the innumerable prejudices and distractions that line our path. They keep us aware of the narrow way that leads to spiritual freedom.

75. When a candidate comes to receive the habit, he is asked what it is he is seeking. He answers that he desires to lead a life of penance. That life of penance is simply this: constant vigilance and self-denial through evangelical poverty, chastity, obedience, stability and unceasing prayer.

CHAPTER 4

Monastic Poverty

76. A monastic community is a family of God. For that reason God himself not only is the Father of the family, but also is the Lord and the possessor of all its property. As sons and daughters of that family the monastics enjoy the use, but not the rights of ownership, of such property. They posses all things in common and also are ready according to their means to share with the poor. We want to follow our Lord Jesus Christ who “being rich became poor for our sake” (2 Cor 8:9).

77. The profession of poverty not only forbids us to posses anything as our own, but also deprives us of any free disposition of material goods. We must make ourselves friends of simplicity, living in common-sense frugality and avoiding all that is excessive. Our cell should always be a place in which the Bridegroom finds pleasure and peace.

78. Many monasteries have perished through accumulated wealth. It requires great care to dispose well of what the community may possess. On the other hand, when times of real want and penury might come, we must say with unshakable confidence: “Blessed be the name of the Lord” (Job 1:21).

CHAPTER 5

Angelic Chastity

79. The grace of chastity affects our entire life, our conduct and general moral character. It implies a life that is straightforward and free of pretense and delusion, thus illustrating at all times the integrity characteristic of virginity.

80. In order to acquire a pure heart it is not sufficient to be chaste. You also must detach yourself from many other things, large and small, which subject you and make you a captive. One may be possessed by other people, by things of the material world, or by spiritual things.

81. The Psalmist sings: “Unite my heart to fear your Name” (Ps 86:9). Jesus repeats this chant and makes purity of heart one of his Beatitudes: “Blessed are the pure in heart: they will see God” (Matthew 5:8). Purity of heart will assure us of the possession of God by ‘seeing’ Him. It gives us, in this world, knowledge of and intimacy with him in prayer.

82. There can be no question of progress without acquiring this purity. It also gives a certain purity of vision in the discernment of spirits, that subtleness which helps us to know what comes from God and what comes from man or from the devil. It also provides wisdom when decisions must be made, because it ensures liberty of judgment and docility to the inspirations of the Spirit. It is the simplicity of eye which gives the whole body the ability to live and to move in the light.

83. In order to acquire and to preserve purity of heart, we – like the ancient monastics – must not fear renouncements, solitude, vigils and fasting. Purity of heart is comparable to the precious pearl of the Gospel. It is so precious that we should, without fear of being mistaken in our action, sell all that we have in order to obtain it.

CHAPTER 6

Obedience and Humility

84. By obedience, we sacrifice to God our most precious treasure: self-will. This sacrifice is the epitome of renunciation. The paradox of this willful surrender is that by it, we are freed in a more profound sense.

85. Obedience is realized in monastic life by voluntary cooperation with the superiors, with the teachings of the spiritual father and with the needs and requests of all together. Obedience means to be attentive, to hear and respond to the voice of the Lord both in ourselves and in our neighbor and surroundings.

86. It is Christ Himself who instructs us in humility when He tells us to learn of Him for He is meek and humble of heart. At the time of reception, these words of Christ are the first addressed by the superior to the candidate for monastic life, and they are read again in the Gospel lessons of that rite.

87. To be humble is to be free of deceptions by being in touch with the simple truth of ourselves. Humility can be likened to a treasury of virtues for, out of humility, love and kindness grow and in their wake all the other virtues as well.

CHAPTER 7

Piety

88. By piety, we understand the monastic practices of silence and fasting in keeping with the tradition of the Church.

89. Through the practice of silence, each of us comes to terms with reality. It is the way to perceive the message and meaning of reality rather than projecting our will upon it. By silence, one learns what it means to listen to others in particular and to reality in general, to perceive and understand, and thus, to grow in wisdom.

90. Silence also means interior quiet and tranquility (hesychasm). Much of the history of monasticism results from this practice of silence which is based firmly on the commandment: “Be still and know that I am God” (Psalm 46(45):10.

91. By fasting from material foods, the monk is made aware of spiritual hunger. Fasting is an ascetic discipline. Furthermore, fasting allows us to be grateful for the food we have.

92. In addition, the Church has traditionally set-aside certain times when monks are bound by greater abstinence. The extent and measure of these fasts are always to be applied by the Hegumen’s discretion according to the condition of the times and the strength of the members of the monastic Brotherhood.

CHAPTER 8

Renunciation of the World

and the Vow of Stability

93. In renouncing the world, we reject what all authentic spiritual traditions have rejected: the emptiness and vanity of the world and its pursuits. At the same time, we aspire to the pursuit rather of the deepest truth, as we are able to meet it in the world in which we live, in the world that Christ has redeemed and which awaits His final coming.

94. Nevertheless, we should not understand by this that monastic life is ever antisocial, for it is itself a social entity.

95. Rather, our renunciation of the world signifies that monasticism is essentially outside the pale of ordinary worldly life and interests. It is principled by a radically different and often opposite outlook and values.

96. Our stability flows from this outlook on the world and its ways, for stability applies not only to the Monastery of one’s profession but to the very way of life that is monasticism. It is characterized by purity of heart, the single-minded pursuit of life in Christ.

97. As an aid to fostering community life, the monks eat at least the main meal together daily. They also spend some time together each evening for relaxation and conversation among themselves. We will observe these instructions more closely on great feast days.

P a r t F o u r

__________________________________________

D E P A R T U R E F R O M

T H E M O N A S T E R Y

CHAPTER 1

Death

98. The words of the profession rite make it perfectly perfectly clear that profession is made for the entirety of the monk’s life. Thus, even with death, one does not cease to be a member of his monastic Brotherhood.

99. When one of us dies, he is given the customary rites. Clothed in his habit with his profession cross in his hands, he is waked in a simple wooden coffin in the monastic temple, and after the funeral rites, he is carried by the Monastics to the cemetery. On the fortieth day after his death, we celebrate the memorial office for his repose, just as we do again on the anniversaries of his death.

CHAPTER 2

Voluntary of Involuntary Departure

100. Only for very serious reasons may a monk be dismissed from the monastic life.

(a) The professed can be dismissed only by due process of ecclesiastical law.

(b) Novices or candidates are dismissed if they do not obtain the approval of the Hegumen and the Council.

101. If a member of our Monastic Brotherhood should ask to leave to join another Monastery, the Hegumen must ascertain the sincerity and character of his motives and, if necessary, he may require the individual to present his motives to the Council for its consideration. If the Hegumen approves the transfer, the individual may leave, provided the Hierarch does not object and the other Monastery is ready to receive him and has issued a Gramota of Inclaustration.

102. If a monk wishes to leave monastic life altogether, the Hegumen should, again, ascertain the nature of his motives. Without unreasonable coercion, the Hegumen should, nevertheless, encourage the individual to re-examine his intentions and former dedication. If, however, he insists on leaving, an Ukas of Secularization must be obtained from the Metropolitan Prime Bishop. If the monk concerned is also in Major Orders, the usual ecclesiastical laws must be observed.

“Preserve the evangelical common life, without possessions, in charity

and humility and patience, in watchfulness and prayer, in obedience

and meekness, in silence and continence, in compunction and tears,

and in other ascetic endeavors, corporal and spiritual. In the observance

of these commandments many of our fathers and brothers who have toiled

much, podvyznyky, our fellow-ascetics, have fallen asleep. Strive to observe

these things with all your soul, to the very end.”

The Spiritual Testament of St. Theodosius of Manjava

-------------------------------

Monastic Chapter February, 1977